Metaphors, in their simplest form, are powerful tools to convey ideas that may be deep, complex or difficult to describe succinctly into a broadly understandable analogue.

Put another way, metaphors draw a comparison between two very different things with the purpose of making a meaningful comment upon one or both of them.

Metaphor appears in many forms. They can be as short as a single sentence:

Art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life.

Or a metaphor can be as long as an entire book, such as a novel where a man is constantly making repairs to a house that’s determined to fall apart, while struggling to hold together a broken marriage, a failed career and children on the verge of delinquency.

Metaphor in art

Some metaphors don’t have to be written. A work of art is often a metaphor for an aspect of life. This is especially true of propaganda.

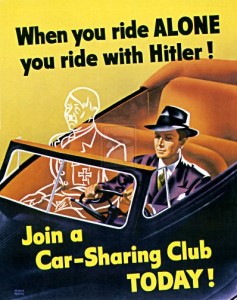

Consider this iconic World War II image of of a solo motorist riding with a ghostly depiction of Hitler, commissioned to encourage carpools and gasoline conservation for the war effort.

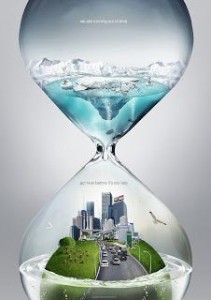

Or take this image of an hourglass with melting glaciers slowly dripping onto a city as a warning about the long-term dangers of global warming.

These examples are heavy-handed, but they demonstrate the concept.

Metaphor in music

Music can be steeped in metaphor as well. Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf is a well-known example of this, with each character represented by a particular instrument and theme. The piece is often performed without the original narration, allowing the story to be told entirely through the movements of the symphony. This technique has become the standard for composition of modern film scores.

It has been argued that the human ability to recognize metaphor is the common basis for all art, and largely responsible for our capacity to learn.

Metaphors offer lots to the writer skilled enough to employ them wisely.

But before we continue…

An important side note about similes and metaphors

We’ve all had a high school English teacher who scolded us that “similes are not metaphors.” That isn’t precisely accurate. It is true that not all metaphors are similes, but similes are, in fact, a form of metaphor. However, the simile is a weak aspect of the form, because it reduces the comparison between objects to a very narrow aspect:

He was like a lizard, cold and dispassionate with others.

This sentence is fine, but an editor with a keen eye will be unimpressed and ask for a rewrite that eliminates the simile, like this:

The man was a lizard whose blood ran cold to compassion for others.

The second is a stronger sentence and imbues lizardness into the whole of his character, rather than just a particular aspect. Depending on how much time we spend with him, we can layer other lizard-like tendencies into further description of his character without having to revisit the comparison.

And on we go with our discussion of metaphor.

In his famous ballad The Highwayman (1906) , Alfred Noyes uses metaphor in the first stanza to establish mood and theme:

The wind was a torrent of darkness among the gusty trees.

The moon was a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas.

In these two lines alone, we know that this is not to be a happy tale.

Dead metaphors

Most clichés are a form of metaphor, but they’re a special, insipid member of the category known as dead metaphors. A dead metaphor is one whose meaning is understood absent of the original intent of the phrase.

Notable examples of dead metaphors include “dialing the phone number,” which is only true if you still employ a rotary phone; or the archaic “world wide web” which was the term we used to describe the internet to our parents 20 years ago. Originally evocative of how the interconnected network of networks is like a spider’s web of information, it evolved to become its own definition of the internet, before we all just decided to call it the “internet” and be done with it.

Dead metaphors don’t provide any of the benefits of a well-crafted original metaphor. Clichés are worse, because they’re simply rehashes of old, tired metaphors that have been thoroughly cleansed of all meaning.

Metaphor: an insight into thinking

That brings us to the most important role metaphors play in your writing: they are your reader’s best insight into how you think. The highest goal of metaphorical language not only is to inform the object of the metaphor, but the thought process that created the comparison itself. It will reveal the author as irreverent, acerbic, brooding, melancholy, or any other possible adjective. The worst it could reveal an author to be is staid or unoriginal. Excise the tumors of static thought.

I briefly mentioned mixed metaphors in my last blog post (link back to preventable errors). Broken clichés are the easiest of these to identify:

He drinks like a chimney and smokes like a fish.

Metaphors require tact

Mixed metaphors draw a false or confused comparison, undermining the intended point and halting readers in confusion.

Like any powerful tool, metaphor is best used with tact. It’s the highlight touch on the important details: the parallel arc that examines the theme in another way. But an over-reliance on metaphorical language will frustrate your reader until they are screaming at you through the page to just spit it out already.

Obvious metaphors will similarly displease your readers. They come across as pedantic and insulting, as though you think the audience too dim to take your meaning. It is not always the easiest balance to strike, as particular audiences will have a different tolerance for them than others–a children’s novel, for example, will have more room for obvious metaphors than literary work aimed at the academic crowd.

For some more reading on the subject, author Chris Wendig has compiled a helpful, and (WARNING to parents) heartily profane, list of 25 things he feels writers should know about metaphors. He expands on many of the issues described here and discusses more key elements of how and why authors use them.

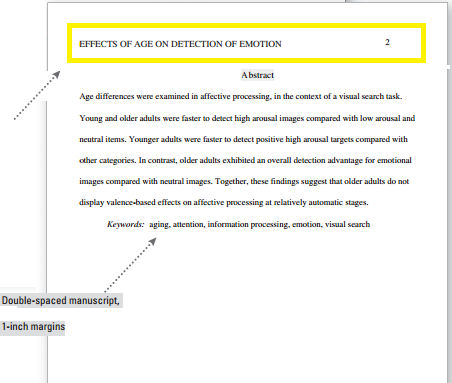

First, the Abstract page is always page 2. Include a “running head” on it (a condensed, 50 character or less version of the title on the left, the page number on the right).

First, the Abstract page is always page 2. Include a “running head” on it (a condensed, 50 character or less version of the title on the left, the page number on the right).