You have thoroughly researched your content. You’ve distilled your arguments into cogent and concise sections.

You have thoroughly researched your content. You’ve distilled your arguments into cogent and concise sections.

You’ve assembled your paper in a manner that implies direct relationships between topics, but your instructor still says you’re missing something, that your paper is “choppy” or that your thoughts “jump all over the place.”

Clearly, your instructor is missing something, right? All of the information is right there, in a straight line, what could be missing?

In this scenario, hopefully your instructor would be kind enough to clue you in to the missing element: transitions.

The train analogy

Transitions can be easy to ignore–because they come so naturally. If your paper is a train, your thesis statement is the engine and your arguments are the cars.

Transitions can be easy to ignore–because they come so naturally. If your paper is a train, your thesis statement is the engine and your arguments are the cars.

Transitions are the links between cars. The cars will still be filled with material, but without the links, they’ll fall away without getting delivered.

The Billy Joel method

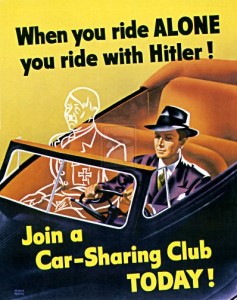

If you are of a certain age, you’ve probably heard Billy Joel’s song We Didn’t Start the Fire more times than you care to imagine.

The song is a perfect example of how removing transitions also removes any meaningful relationship between topics.

Do Sputnik and Chou en-Lai have anything in common? Maybe, but you wouldn’t know from the song.

REM “logic”

A better example is REM’s classic It’s the End of the World.

What does Leonard Bernstein have to do with anything? No one knows. Just sing the chorus.

Linear thoughts don’t always translate to paper

While transitions typically come naturally in linear thought, there are many ways they can become lost in constructing a paper. Often times papers are not written in a linear fashion, or the order of arguments will be shifted from one draft to another. A transition appropriate from one argument to the next might not work when the order is rearranged.

While transitions typically come naturally in linear thought, there are many ways they can become lost in constructing a paper. Often times papers are not written in a linear fashion, or the order of arguments will be shifted from one draft to another. A transition appropriate from one argument to the next might not work when the order is rearranged.

When sections of a group project are individually crafted, the leader of the group needs to craft reasonable transitions between one person’s thoughts and another’s to illuminate the greater purpose of the paper.

Haste makes…I forget

Writing too quickly can lead to logic leaps that make sense in the writer’s brain but will leave readers wondering how topics relate. This can happen when the writer has a very clear understanding of the topics or arguments they want to cover, and they want to get them all into the document before they forget any of them.

This can also happen when “the perfect sentence” pops into the writer’s mind. The goal then shifts to getting all of the perfunctory writing out of the way before the sentence is lost in the hollows of the mind.

The best way to avoid mistakes caused by writing too quickly? Keep a detailed outline of your paper.

Inside your outline, you can use shorthand markers to get to the better-formed thoughts, allowing you to write in as little or as much detail as you like before worrying about the specific ways to connect your thoughts.

If you work exclusively within a word processor, it’s not a bad idea to keep a good ol’ pen and paper on hand to scrawl out a spontaneous epiphany without having to worry about switching back and forth between your outline and main document.

Words, phrases, sentences

Transitions take a handful of forms across a multitude of categories. The forms include these transitional words:

but

while

then

Transitional phrases:

in this scenario

for that purpose

Or transitional sentences:

Clearly, your instructor is missing something, right? All of the information is right there, in a straight line, what could be missing?

The University of Wisconsin and Michigan State both have an excellent compilation of transitional words and phrases broken down by contextual category.

Transitions serve as the signposts of logic within a text. They don’t describe a thought or argument specifically, but they do illustrate how thoughts and arguments are connected and therefore related, or not.

Without them, your paper will be no better than a Billy Joel song. You’re better than that. I know you are.

For further reading, UNC-Chapel Hill has a terrific virtual handout that digs deeper into the specifics of transitions and transitional expressions.

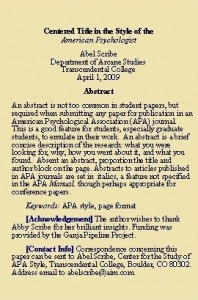

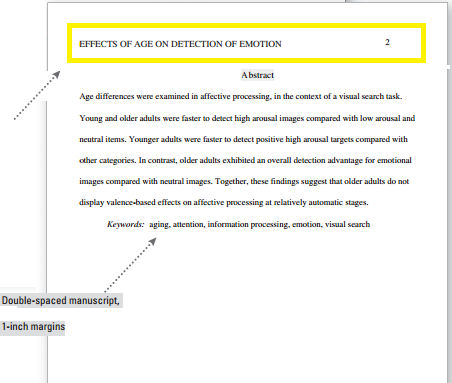

First, the Abstract page is always page 2. Include a “running head” on it (a condensed, 50 character or less version of the title on the left, the page number on the right).

First, the Abstract page is always page 2. Include a “running head” on it (a condensed, 50 character or less version of the title on the left, the page number on the right).  Do you lack the motivation and energy to complete tasks (especially “boring” ones)? This can be a frustrating no-end battle for people with ADHD and other self-regulation spectrum conditions (autism is a condition that can impair your ability to get things done, too; sometimes

Do you lack the motivation and energy to complete tasks (especially “boring” ones)? This can be a frustrating no-end battle for people with ADHD and other self-regulation spectrum conditions (autism is a condition that can impair your ability to get things done, too; sometimes  If you live with a condition like ADHD, you know that you’re not dumb, lazy, or unwilling, even if other people might label you in this way. It might not take much physical/mental activity to exhaust you. ADHD is neurobiological, so you’re NOT imagining things. You feel lousy and have trouble keeping up with life’s demands because you have a real condition. Read

If you live with a condition like ADHD, you know that you’re not dumb, lazy, or unwilling, even if other people might label you in this way. It might not take much physical/mental activity to exhaust you. ADHD is neurobiological, so you’re NOT imagining things. You feel lousy and have trouble keeping up with life’s demands because you have a real condition. Read

Now July 1 may be have been a washout from every angle—but at least when you look back on it in your diary, you will know why:

Now July 1 may be have been a washout from every angle—but at least when you look back on it in your diary, you will know why:  Once you keep a daily record of these variables, you should begin to see some patterns after a few months. Your reward—you should be better able to predict when to “schedule” more cognitively demanding activities like writing papers.

Once you keep a daily record of these variables, you should begin to see some patterns after a few months. Your reward—you should be better able to predict when to “schedule” more cognitively demanding activities like writing papers.  If under scheduling is just too unrealistic, make it a priority to at least eat properly (please see below), sleep sufficiently, exercise as much as you can stand, follow a structured routine, and if you know toxic people/situations/places that trigger stress for you, avoid or minimize exposure if possible.

If under scheduling is just too unrealistic, make it a priority to at least eat properly (please see below), sleep sufficiently, exercise as much as you can stand, follow a structured routine, and if you know toxic people/situations/places that trigger stress for you, avoid or minimize exposure if possible.  Regular sleep patterns with relatively little deviation over weekends are essential in managing your condition. You know what happens when you stay up until 3 a.m. on a weekend when you are accustomed to an 11 p.m. bedtime during the work/school week. Monday morning will be even more of an ordeal, and you’ll likely feel irritable and exhausted. You will then be tempted to turn to heavily caffeinated and/or sugared fixes for a temporary boost and subsequent crash.

Regular sleep patterns with relatively little deviation over weekends are essential in managing your condition. You know what happens when you stay up until 3 a.m. on a weekend when you are accustomed to an 11 p.m. bedtime during the work/school week. Monday morning will be even more of an ordeal, and you’ll likely feel irritable and exhausted. You will then be tempted to turn to heavily caffeinated and/or sugared fixes for a temporary boost and subsequent crash.

With ADHD and similar conditions, if you underestimate what you can do in a period of time, you will probably get it just right. Imagine that a task will take 3 times as long to finish, and you may be pleasantly surprised to find you have finished it sooner.

With ADHD and similar conditions, if you underestimate what you can do in a period of time, you will probably get it just right. Imagine that a task will take 3 times as long to finish, and you may be pleasantly surprised to find you have finished it sooner.  This strategy has been legendary for keeping people (especially easily distracted people) on task. Why do bosses exist in most workplaces? In large part, bosses babysit. When you go home, you sometimes need a sitter there, too.

This strategy has been legendary for keeping people (especially easily distracted people) on task. Why do bosses exist in most workplaces? In large part, bosses babysit. When you go home, you sometimes need a sitter there, too. If you have ADHD or a similar condition, you may be familiar with having multiple sensitivities, and gluten intolerances are not uncommon to people who complain about an inability to focus and complete tasks. A high complex carbohydrate, moderate protein, low simple carbohydrate, sugar free diet may be helpful.

If you have ADHD or a similar condition, you may be familiar with having multiple sensitivities, and gluten intolerances are not uncommon to people who complain about an inability to focus and complete tasks. A high complex carbohydrate, moderate protein, low simple carbohydrate, sugar free diet may be helpful.  This is also known as the “caveman diet.” Ask yourself if our ancient ancestors suffered with ADHD, chronic fatigue syndrome, autoimmune diseases, joint pains, arthritis, rashes, and other “modern” diseases.

This is also known as the “caveman diet.” Ask yourself if our ancient ancestors suffered with ADHD, chronic fatigue syndrome, autoimmune diseases, joint pains, arthritis, rashes, and other “modern” diseases.